Sid Meier’s Civilization was one of the most addicting games of my life. I feel like I could have learned several new programming languages in the weeks and months I spent building pixelated empires, warring with foreign nations, pursuing brand new technology, and losing everything in an inferno of digital destruction. I was pleasantly surprised to hear that Iain M. Banks shared the addiction and that his Culture novel Excession was in part inspired by it. In an interview with SFX Magazines, Banks said:

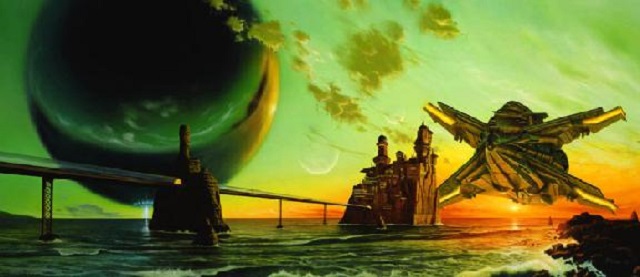

“Inventing a world where you have different laws of physics, that would be about the ultimate version of Civilization. That’s part of where the idea of Outside Context Problems came from, you’re getting along really well and then this great battleship comes steaming in and you think, well my wooden sailing ships are never going to be able to deal with that. But when I started Excession I deleted Civilization off my hard drive.”

Excession is one of my favorite Culture books and I loved the way it focused on the Minds and the mystery behind the excession itself. The humans, though, seemed like they were tacked on, unnecessary accessories that distracted from the main attraction (I especially struggled with Ulver Seich, who threw a fit for not being able to bring her furry pets on a mission for Special Circumstance). It was only when I viewed them from the context of Civilization that the book took on an entirely different meaning.

Outside Context Problem

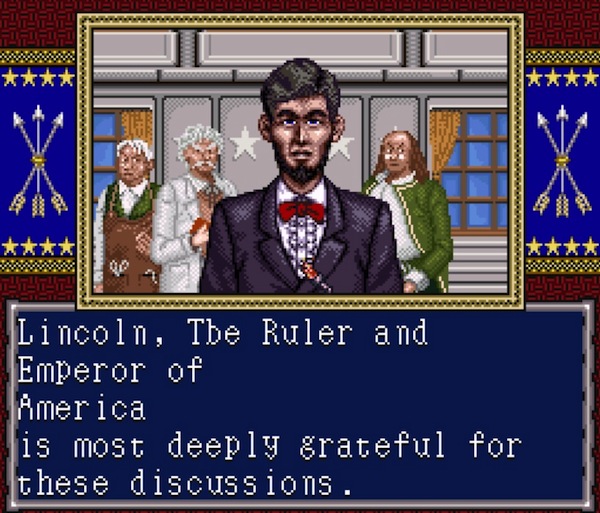

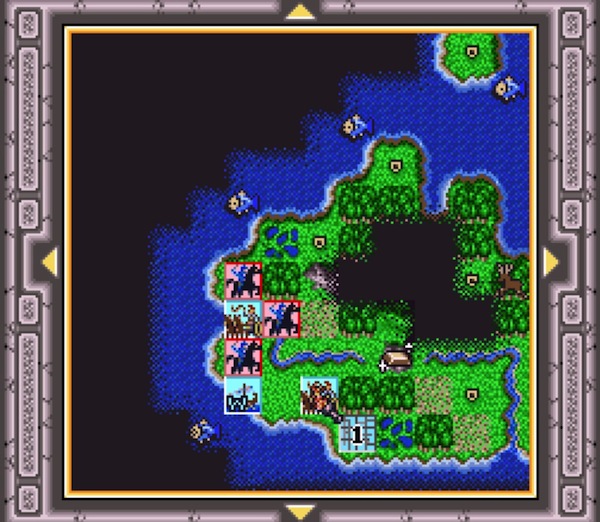

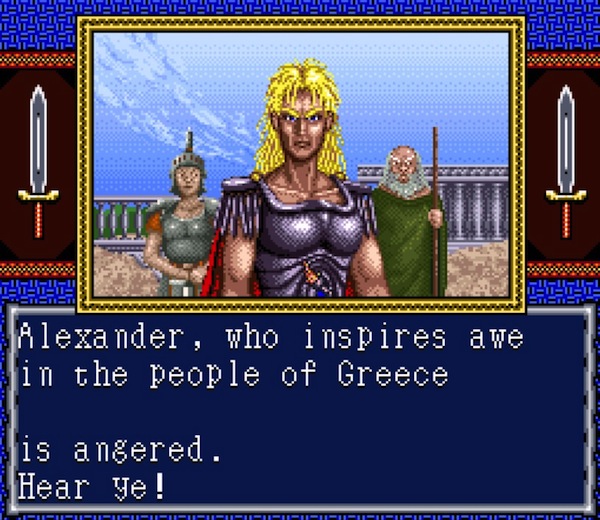

Civilization was developed by MicroProse and the original DOS version was released in 1991 (the screenshots in this article are from the Super Nintendo version though the gameplay is more or less identical). Designed by Sid Meier, it was an evolution of his earlier game, Rail Tycoon, that also incorporated elements of the board game with the same name, Civilization. In essence, you begin at the dawn of humanity, take a group of settlers, build an empire, and engage in turn-based strategy that can best be summed up in the 4X philosophy: eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, and eXterminate. Civ, as people often called it, sucked away countless hours of my life. I was always trying to take one extra move, conquer one more city, and buy an additional building. That additional turn quickly became a whole evening and often seeped into the early morning. Creating another road, setting up irrigation, chasing after the wheel so I could create an army of chariots, moving another pair of units on a trireme while keeping it close to land, dispatching soldiers to take care of a landing party of barbarians, and carefully navigating my way around an alliance with the Egyptians was all part of the campaign. Alternative histories never had so many alternatives. In one timeline, the Roman Empire never fell and lasted until the space age. In another, the Aztecs built atomic bombs.

I first heard about the game from friends who regaled me with stories of their global conquests. Everyone had a different story, a narrative complete with arc, twist, and denouement. It was like a childhood Chautauqua, kids gathering around and swapping Civ stories, tips, and tragedies. My imagination ran wild as I heard about the wily AI, the race for arms, the espionage and all-out combat. I have to admit, I was somewhat disappointed when I first saw the graphics as they were so basic compared to everything I’d conjured in my head. Ironically, the primitive graphics ended up working better because they served as symbols rather than literal interpretations of the forces at work, spurring my imagination as it had my friends. Meier was said to have made it more heavily text based in initial versions, but went back to a more graphic gameplay because it was more entertaining.

Civ taught me the basics of nation building through practical application in a way most history books could only scratch at. Cities would thrive based on location, proximity to bodies of water, and the infrastructure. They couldn’t grow beyond a certain limit without aqueducts in place, but the people also needed entertainment in the form of a colosseum and a temple in order to be happy. Revolutions changed governments, I stomped out rebellions using my military, and often went to war against foreign nations even if my people did not wish it. Depending on the difficulty level I chose, one of the toughest parts of the game was when I’d spend hours building a civilization, connecting the cities together, trying to guide it into a new age, then have enemy ships arrive with militia men and guns. My swords and spears were no match for them and I’d reluctantly wave the flag, acknowledging it was time to restart.

Everything in Civ is on the macroscopic level. But I got to thinking, what if I actually could know the ramifications of my actions and the impact they had at the individual level? What if my decision to attack Macedonia instead of honoring the peace I’d agreed to actually led to the death of soldiers with families? What if at the moment when my entire civilization was exterminated, I had to feel their individual pain?

As much as Excession was about the anomaly, it was also about a Mind, the Sleeper Service, who felt guilty for one of the decisions it made on a galactic version of Civilization. It was that realization that led me to me rethink the entire book.

The Land of Infinite Fun

One of the most fascinating ideas in Excession involves a game the Minds play with themselves called metamathics. They “imagined entirely new universes with altered physical laws, and played with them, lived in them and tinkered with them, sometimes setting up the conditions for life, sometimes just letting things run to see if it would arise spontaneously, sometimes arranging things so that life was impossible but other kinds and types of bizarrely fabulous complication were enabled.”

Part of the joy of Excession is hearing the Minds speak with each other, that matrix-like shower of numbers, text, esoteric syntax, and witty repartee. The Minds are generally a benevolent force, calculating and prancing through the complexities of intergalactic politics. Each has a distinctive personality, their own codes and quirks they abide by (I refrain from saying “eccentricities,” as Eccentrics are a class all to their own in the Culture). The rapid communication exchanges are triggered by the discovery of a “dead star that was at least fifty times older than the universe” that could potentially give them “an entire universe” that “would be yours alone. In fact, go back far enough-that is, to a small enough, early enough, just-post-singularity universe-and you could, conceivably, customize it; mold it, shape it, influence its primary characteristics.” It’s like the ultimate game of Civilization Banks’ referred to in his interview.

The novel has a frenetic pace, jumping through multiple sides like a turn-based strategy game. The Elench, the horrible Affront who take pleasure in inflicting pain (“Progress through pain” being their creed), the Minds, and Dajeil and Genar-Hofoen each take a turn. On my initial read, I didn’t find Dajeil and Genar’s relationship as compelling or interesting as the individuals in some of the other Culture books like Player of Games and Use of Weapons, especially as their romance was based almost solely on physical attraction. Considering that everyone in the Culture can gland and change their appearances, that fact amplified the shallowness of their bond. The pair felt like excess in a story packed to the brim with intrigue and universe-shattering possibilities. Genar cheated on her in the past, resulting in a violent breakup in which Dajeil attacked Genar. Afterwards, Dajeil withdrew from society and put her pregnancy on indefinite hold. The Sleeper Service felt responsible for their fallout, and many of the actions it undertakes in the book are its way of atoning for its choices. As it states: “Sometimes you take a hand in such stories, such fates. Sometimes you know or anticipate the extent to which your intervention will matter, but on other occasions you don’t know and can’t guess. You find that some chance remark you’ve made has affected somebody’s life profoundly or that some seemingly insignificant decision you’ve come to has had profound and lasting consequences.”

The Sleeper Service feels culpable for its choice on a level most other Minds would barely countenance, and one players of Civ surely never would. Towards the end, when it actually helps unite the two for a brief moment, it’s a strangely haunting sequence that reminded me that the AIs of the Culture are often more human than the humans themselves. It also helped me to realize that the personalities of the humans weren’t as key to the book as the emotional OCP it posed for the Sleeper Service. Genar and Dajeil’s arc isn’t convincing (I won’t even get into Ulver here), but that’s unimportant. It’s Sleeper Service who awakens, Sleeper Service who has to make its peace with its past.

The book wraps as the Excession reacts defensively to the Culture forces until the Sleeper Service ends up transmitting a copy of its mindstate to the Excession. As both the Sleeper Service and Dajeil were previously frozen (the former in gestation for Special Circumstance and the latter in pregnancy), the Excession too was in waiting. Unlike Sleeper Service, who tries to help resolve the issue for Dajeil, the Outside Context Problem is resolved by the awareness that the Culture is not ready for whatever it is the Excession was going to provide. It leaves peacefully.

Enemies in Civ tend to be a lot less forgiving.

The Interesting Times Gang

These are, of course, just some of my speculations. Often, as these things go, it’s easier to connect the dots after the fact even if the correlation at the actual moment of execution was minimal. As one of the Minds points out: “The closer one looks into anything the more coincidences one finds, perfectly innocent though they may be.”

I loved Excession on so many levels, and the admiration has grown with a third reading. There are literally paragraphs thrown in as background detail that could make for amazing novels of their own. If I were to get into a deeper discussion of what I enjoyed so much about it, I would go on forever, so I’ve limited myself to the connections between the book and the game. I only have two Culture books left (Hydrogen Sonata and Surface Detail) and I’m trying not to rush in reading them. But the interplay of the Minds is something I hope I’ll get to see again before my time in the Culture universe is complete. One thing Civilization made me rethink was my stance on time, seeing it more from the Mind’s perspective. In Excession, the conspiracy to rid the Culture of the Affront was hundreds of years in the making, beginning with the bait of Pittance around the time of the Idiran War. It might seem a long time, but in Civ, a few hundred years is nothing in the grand scope of things and I’ll often plan things out centuries before they happen. I’ve wondered what it would be like if my perception of time was as broad as a Civ interface…

Both Civilization and Excession are fantastic works, and their intersection, whatever its extent, goes to show how powerful gaming can be. It’s not just fiction influencing gaming, but vice versa. With all the recent trends pointing towards an explosion of virtual reality, my question is, when is someone going to make a metamatics simulator, a chance to recreate and play Civilization with the whole universe? I credit Excession for forcing me to ask from the outset: what are the ethics behind it? What are the moral ramifications?

Peter Tieryas is a character artist who has worked on The Good Dinosaur, Guardians of the Galaxy, and Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs 2. His novel, Bald New World, was listed as one of Buzzfeed’s 15 Highly Anticipated Books as well as Publisher Weekly’s Best Science Fiction Books of Summer 2014. His writing has been published in places like Kotaku, Kyoto Journal, and ZYZZYVA, and he blogs at tieryas.wordpress.com and tweets @TieryasXu.